As I made my way through the thick, midnight fog, I felt electric. The cobblestones cli-clacked beneath my boots, a syncopated rhythm which made my blood dance. The door in front of me was a tangled relic, a mass of metal and wires and wood and stone. I lifted the ancient knocker but before I could apply enough force to engage it with the worn groove in the decaying wood, the door slowly creaked open….making the only sound such a door could make. Music poured into the night. Pulsating beats oddly juxtaposed under an old standard. Lulling vocals. An upright base competing wth a drunken accordion. I entered. Inside, towards the back of the joint, a single table. A swinging lamp, shadeless, dim bulb, filtering light through heavy smoke and expectations. And beneath it sat the man I’d come to meet.

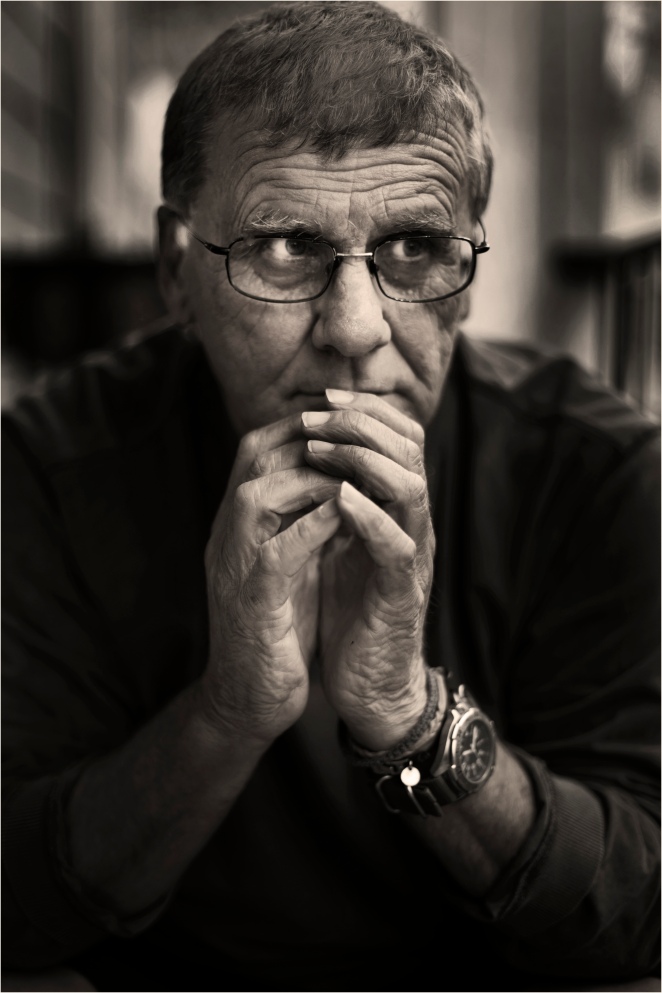

Jack Barnosky

“Hello, Jack,” I muttered out the side of my mouth in affected staccato.

And the whisky smooth retort came in a deep, mesmerizing baritone, “Ms. Peters, I presume.”

This is how it happened. Where I traveled to interview one of my favorite artists, Jack Barnosky. This is the exact account….if it had taken place in one of his phenomenal images.

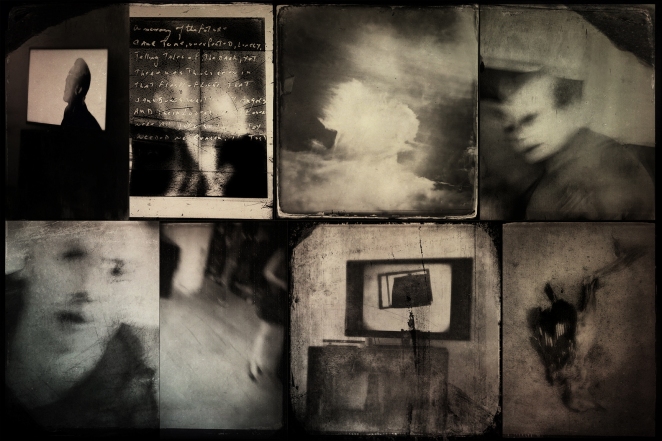

Deep, rich, complex. Focused, concise, definitive. Barnosky’s work relays the decades of passion and expertise he has amassed. And like the man, it lures you in without pretension; invites you to get comfortable and stay awhile; yet leaves you wanting, hungry for more. Barnosky has a way of stripping away all of the bullshit and window dressing. What remains, however, is somehow more elaborate, more compelling, even more mysterious.

ISWE: I understand you were an avid and well educated analog photographer. Can you talk a bit about your early photography? What brought you to this art? What were you trying to say?

JB: I was both. Analog was the only way to make photographs. The only variables came in format choices and the many ways of dealing with printing in the darkroom. I first made photos while at Ft. Dix N.J ( p.f.c Barnosky NG239423770 ret.) in 1967. It was a wartime army so there wasn’t much time for extra curricular activity. After my REFRAD ( release from active duty) I went to West Chester State University and majored in fraternity parties. I did not have the desire or skills to be a serious student. So I decided to be a reporter and went to the student newspaper office and was told I could be a photographer. So I became a photographer.

Two years later I was wandering the streets of Philadelphia with my trusty double stroke Leica M3 and to get out of a blizzard I ducked into the Philadelphia Museum of Art. As fate would have it there was a photo exhibition. One of the Photos was Moonrise, Hernandez New Mexico by Ansel Adams and I immediately fell in love. I did not realize that photographs could look like this, could convey so much emotion. Could be the real world. I was nailed to the floor in front of this photograph. I could feel the wind off the mountain. I could hear children playing and dogs barking. I could smell the beans cooking. I didn’t realize at the time but my life had changed forever. I never again wanted to do anything but make photographs. I had plenty of jobs. I made bricks for a year, but always was making photographs.

Early on I had nothing to say, at all. I was just enamored with the medium, and the medium was the message.

ISWE: Who and what influences your work?

JB: At about the age of 12 I discovered the art of Richard Powers. He was a commercial artist who made cover illustrations for paperback science fiction novels. He created fantastic worlds. Worlds that I wanted to visit and explore, but I was stuck in Philadelphia.

I’m not a museum guy. I know I’m supposed to be but I’m just not that. I’ve been to Paris 7 times and haven’t spent 4 hours in the Louvre. When I travel the point is to be wandering the streets making photographs. In Madrid I did the entire Prado in an hour and a half. Just down the road from the Prado is the Musee Sofia and this is different. This is where you can see Picasso’s Guernica and this was important. I stayed and sat and looked for hours and went back time after time. Picasso and his gang, Braque etc. are an influence along with all the other surrealists. Like Richard Powers they created worlds of wonder that I still could not visit. The only way was to create my own.

Photographically it has to be Jerry Uelsmann. Because of his work and his ideas about “post-visualization”, Robert Frank for his apparent disdain for rules and, of course, Gary Winolgrand for his lack of restraint and his honesty.

ISWE: Tell us about your transition from analog to digital.

JB: As I said the darkroom was the only way to make photographs. I was never really very comfortable in the darkroom. I never got that “Zen Awareness” feeling that so many people talk about. It was work and I was in there for almost 40 years. The blue collar attitude of just getting up and going to work prevailed. I got pretty good at it. I was using an 8×10 camera and either contact printing or enlarging with an ancient 8×10 enlarger that I found in a pawnshop in Indianapolis. I lugged that big camera everywhere. Deserts, mountains, Paris, London, New York City, everywhere.

After many years something happened that changed my path. One day I discovered that the paper manufacturer, Agfa, had altered the formula for the paper emulsion. Now nothing worked the way I was used to it working. For me it was the day the darkroom died. So I went in a different direction, alternative processes. Platinum, palladium, gum, salt, van dyke and on and on. I even did dye transfer prints but still couldn’t get what was in my head onto a piece of paper. Digital photography was coming on but I resisted. I preached film in class. I was just afraid of digital photography. I would have to learn a new language and I’m a slow, reluctant learner. So I had come to a fork in the road and you know what Yogi said, “ When you come to the fork in the road, take it”. I went all in digital. Haven’t been in the darkroom since 2007. Film IS dead, but the darkroom is alive and well thanks to enlarged negatives via Pictorico. It’s not enough to get me back in the darkroom but maybe , just maybe I’m thinking about it.

ISWE: Your work seems to effortlessly possess a haunting, disintegrated quality that so many photographers crave to produce. What are your go-to tools these days? Camera(s), Editing software/apps, lenses, Etc… Whatever you’re willing to share.

JB: I mainly use an I Phone 6S+ and a Leica C. I’ve rigged the I phone so I can use a MOMENT case. This provides a shutter release where it should be, at my index finger. I always have a DXO camera attached to the I Phone. This is a very powerful little camera that gives about 22 mp. Also I will have a Sony Smart lens attached. The shutter releases for the DXO and Sony lens are on the Apple Watch. All this equipment plus extra batteries etc. can all fit in a small man purse. I’m awaiting delivery of the LIGHT/Camera. This is supposed to be revolutionary. It is the size of an I Phone but with a complete array of controls and 52mp. I hope it works, it was a bit pricey.

I have perhaps 100 apps on the phone but now I use only 2 consistently, Snapseed and Hipstamatic. Most Apps have 1 or 2 things on them that I find usable and the rest is detritus. I will make overlays from apps though. Photograph a piece of white paper, run it through the apps. I save what I like and put them on the computer to be used as overlays, texture screens etc. I always use Photoshop and encourage students to do the same. Many if not most students prefer Lightroom. Go figure.

ISWE: How do you generally approach your work? Do you plan it out in advance or do the subjects catch your eye and inspire you? Is it personal, global, somewhere in between?

JB: Generally speaking I do not plan out the work. Sometimes just a bit. Last semester I asked students to pose in the studio. I was just after faces. So in this case I was collecting faces, expression and I would deal with them later in PS. Yes, subjects catch my eye and I photograph them. This hardly conceptual in nature but it works for me. Sometimes I think of my photos as raw ore that has been mined. Later this ore will be transformed into something else. As far as what inspires me I’ll say all of the above. I’ll defer to the great Chuck Close when it comes to inspiration. “Inspiration is for amateurs.” His statement is much more extensive and it is easy to find.

ISWE: You’re a professor as well as a producer of art, negating the old adage that ‘those who can’t, teach’. How do you feel that teaching others has affected your own work?

JB: “Those that can’t do, teach; those that can’t teach, teach gym” Woody Allen. Every semester, every academic year is new, a fresh start. I’m always changing class content and seeing new enthusiastic students. Well mostly enthusiastic. I’m not a lecturer or a philosopher so all my classes are Lab classes. I’ll demonstrate and show a particular process or idea and then the students are to expound on this in their own voice. This makes teaching very interesting.

I’m very fortunate because I do see different points of view daily. I cannot help but be affected by this. I’m good with that. You learn in many different ways. Being in a room of like minded individuals doing and discussing work is formative and changing. My work is open to critique by students just as their work is open to critique from their peers and myself. What they say can matter. Sometimes profoundly. I listen and filter things but will act on suggestions, sometimes. Just because I stand at the front of the classroom does not mean I am immune from the objective analysis.

ISWE: I know that you identify as a ‘left leaning secular humanist democrat’. How does this come to bear on your work?

JB: Both my grandfathers were Pennsylvania coal miners. They came to this country because they were promised a better life. They were cheated. They worked 12 hour days, 6 days a week in the mines. They never got that promised better life. My parents were New Deal Roosevelt Democrats. My mother worked in factories, school cafeterias anywhere to get a pay check. During WWII my father was a Union welder in the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. After he left the Shipyard he spent 2 years working at night and on weekends building a house because he didn’t want a mortgage. I have campaigned for every Democratic presidential nominee since JFK. All this points to the fact that I was raised without an idea of entitlement. None at all. Zero. So, I have to work for anything that I want. Photographs included, and I do. Daily, six days a week. Saturday is “ date day” ( you have to give in a bit sometimes).

ISWE: Tell us a few photographers who we should study.

JB: Study no one. Study your own work. Looking for some sort of inspiration that does not come from within you is futile. I’ll make one exception here. Watch the documentary “Born into Brothels”, study these children photographers. They live in the lowest circumstances imaginable. They are unschooled and naïve. They know nothing about f stops, shutter speeds, Edward Weston, D Max, color balance etc. etc. Yet they make wonderful photographs. Perhaps there is a lesson here. Perhaps the baggage associated with photography is not needed. Watching the film changed me. I think it is a must see for anyone who would presume to make art.

ISWE: Thank you so much for letting us into your world. Can you leave us with an impression specifically about any one of your images. What inspired it? Was it planned? Was there a message attached? How did you get from the original photo to the current image? Anything you’d like to say…

JB: I’ll throw a bit of a curve ball here. Going back 30 years. Jeddo Pennsylvania Coal mine 22

I spent much of my childhood in this environment. My grandparents lived here so the summers were usually devoted to climbing the hills and exploring the landscape. Later in life I wondered if the child’s memory of this area was fanciful or were my memories accurate? So I went back and found out. I discovered that the vastness and bleakness of this area was not imagined. It was real and more so than I remembered. I spent a few years working here. All done with an 8×10 camera. My message is not an environmental one. It is simply about the people who worked and died here, generation after generation. Of course I could not photograph those people. I could not go back and photograph that distant era. I could only photograph what was left. All my coal mine photographs were planned. I usually knew where I was going. They were all done using the Zone System and printed, lovingly, in a regular old darkroom.

All images remain © Jack Barnosky and were used with explicit permission from the amazing man himself.

I love your work.

LikeLike

Thank you very much 😊

LikeLike